- Topic1/3

54k Popularity

13k Popularity

44k Popularity

2k Popularity

987 Popularity

- Pin

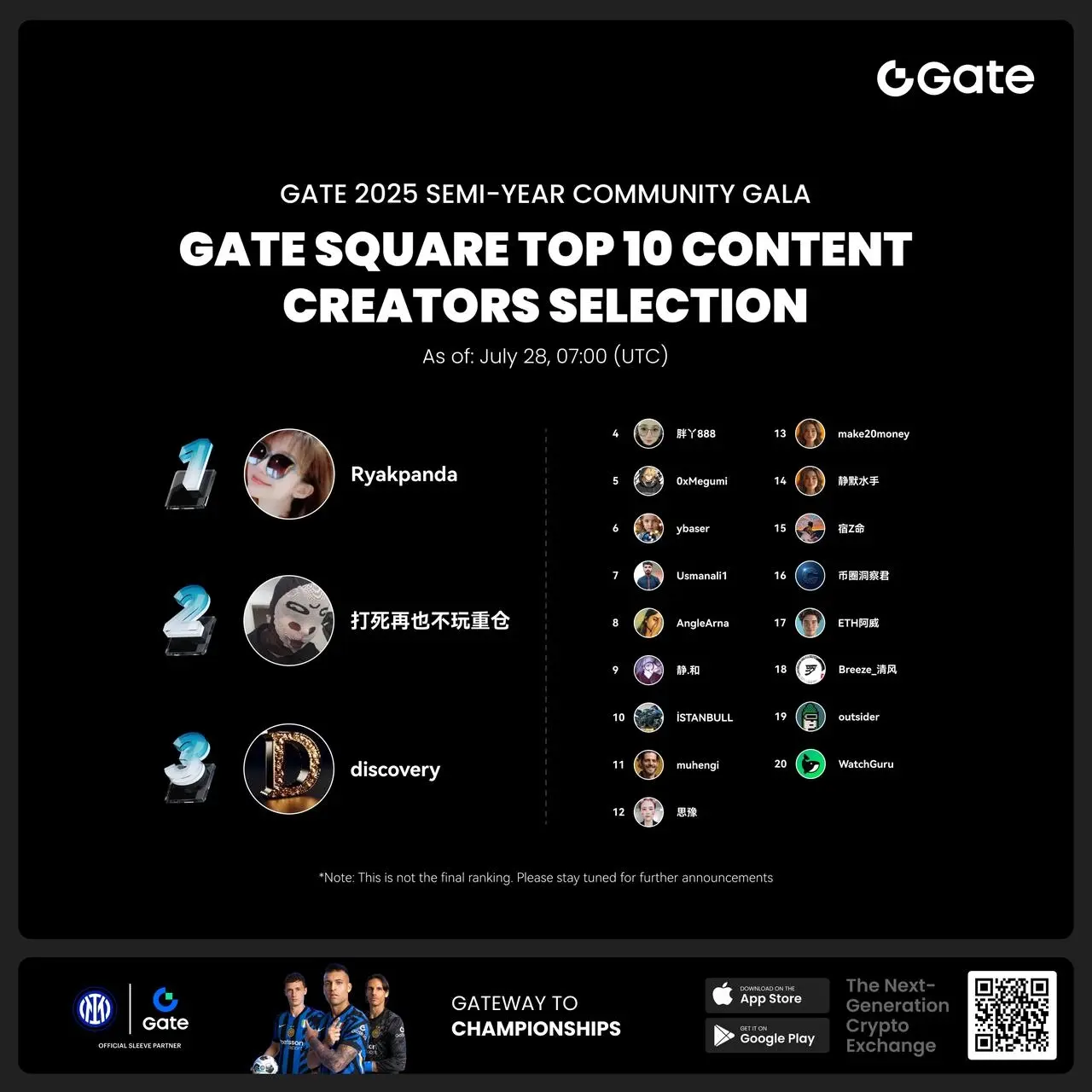

- #Gate 2025 Semi-Year Community Gala# voting is in progress! 🔥

Gate Square TOP 40 Creator Leaderboard is out

🙌 Vote to support your favorite creators: www.gate.com/activities/community-vote

Earn Votes by completing daily [Square] tasks. 30 delivered Votes = 1 lucky draw chance!

🎁 Win prizes like iPhone 16 Pro Max, Golden Bull Sculpture, Futures Voucher, and hot tokens.

The more you support, the higher your chances!

Vote to support creators now and win big!

https://www.gate.com/announcements/article/45974

- 🎉 Hey Gate Square friends! Non-stop perks and endless excitement—our hottest posting reward events are ongoing now! The more you post, the more you win. Don’t miss your exclusive goodies! 🚀

1️⃣ #ETH Hits 4800# | Market Analysis & Prediction: Boldly share your ETH predictions to showcase your insights! 10 lucky users will split a 0.1 ETH prize!

Details 👉 https://www.gate.com/post/status/12322612

2️⃣ #Creator Campaign Phase 2# |ZKWASM Topic: Share original content about ZKWASM or its trading activity on X or Gate Square to win a share of 4,000 ZKWASM!

Details 👉 https://www.gate.com/post/st - 📢 Gate Square #Creator Campaign Phase 2# is officially live!

Join the ZKWASM event series, share your insights, and win a share of 4,000 $ZKWASM!

As a pioneer in zk-based public chains, ZKWASM is now being prominently promoted on the Gate platform!

Three major campaigns are launching simultaneously: Launchpool subscription, CandyDrop airdrop, and Alpha exclusive trading — don’t miss out!

🎨 Campaign 1: Post on Gate Square and win content rewards

📅 Time: July 25, 22:00 – July 29, 22:00 (UTC+8)

📌 How to participate:

Post original content (at least 100 words) on Gate Square related to

Cross-border RWA Success Story: Deconstructing the Compliance Architecture Behind Hong Kong Monet...

Institutional Innovation Over Technology: WFOE revenue rights isolation architecture enables compliant cross-border tokenization, reducing financing costs from 8.7% to 5.2% for energy infrastructure assets.

Two Chains One Bridge Solution: Ant Chain’s cross-border infrastructure uses ZKP to transmit desensitized value data while keeping sensitive information onshore, solving data sovereignty issues.

SME Financing Revolution: 83% of previously unbanked charging pile operators gained access to financing through IoT data credit scoring, replacing traditional collateral-based lending models.

China’s first cross-border new energy RWA breaks through regulatory barriers. Longshine Technology tokenizes 9,000 charging pile revenue rights, raising 100M yuan in Hong Kong’s HKMA sandbox with innovative compliance architecture.

5.INDUSTRIAL VS AGRICULTURAL RWA DIVIDE: WHY DO INDUSTRIAL ASSETS DOMINATE AGRICULTURE?

China’s RWA practice presents two differentiated paths: cross-border tokenization of physical asset revenue rights represented by Longshine Technology, and localized packaging of agricultural data assets led by the Malu Grape project.

Although both bear the name “RWA,” they form distinct divisions in asset anchoring logic, compliance strategies, and liquidity design, reflecting China’s characteristic regulatory adaptability and industry compatibility differences.

5.1DIFFERENTIAL MIRROR: RWA PRACTICE DIVISIONS BETWEEN INDUSTRIAL AND AGRICULTURAL ASSETS

5.1.1Asset Anchoring: Cash Flow Rigidity vs Data Premium Elasticity

Core difference: Longshine uses verifiable physical revenue rights as the core of token value, while Malu separates revenue rights into SPV equity structure, with its NFT serving merely as consumption certificates, forming a fragmented state of “revenue rights belong to shareholders, usage rights belong to users.”

5.1.2Liquidity Mechanism: Cross-border Capital Circulation vs Domestic Closed Loop

Malu sacrifices token financial attributes to avoid the “Notice on Preventing Token Issuance Financing Risks,” with its NFT circulation being restricted and lacking revenue distribution functions. Although Longshine is limited by Hong Kong SFO regulations (6-month lock-up period), it retains on-chain trading possibilities.

5.1.3Governance Architecture: On-chain Automation vs Centralized Decision-making

The Malu project’s proclaimed “on-chain governance” is actually traditional centralized decision-making, while Longshine reconstructs the financing credit system for small and medium operators through IoT data.

The Longshine paradigm validates the feasibility of “cross-border revenue rights isolation + off-chain compliance mapping,” with the cost being liquidity discount (10% issuance cost), but providing sandbox samples for policy optimization (such as Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission adding simplified disclosure clauses for new energy).

The Malu path reveals that in a strong regulatory environment, agricultural RWA needs to exchange “de-financialization” compromise for survival space. Its consumer NFT is essentially a pre-sale card and brand tool, with data asset revenue rights still trapped in traditional equity structures.

Both point to the core proposition of China’s RWA: technology must serve physical value creation under regulatory frameworks, rather than idealized financial liberalization.

5.2 MECHANISM DECONSTRUCTION: TRIPLE COORDINATED CONSTRAINTS

The fundamental reasons causing differences between the Longshine charging pile project and Malu grape project are structural divisions formed by the superposition of policy constraints, asset attributes, and technical paths, which can be specifically deconstructed into the following core contradictions:

5.2.1Policy Constraints: Cross-border Financial Opening vs Mainland Strong Regulation

Longshine leverages Hong Kong’s financial liberalization policies to achieve “true revenue rights tokenization” (ERC-1400 security tokens). Malu, under mainland policy pressure, is forced to decompose RWA into “NFT consumption rights + SPV equity revenue,” forming a compromise architecture of “on-chain shell, traditional core.”

5.2.2 Asset Attributes: Strong Financialized Assets vs Non-standard Physical Assets

Charging piles have a strong financialization foundation—stable cash flow + insurance credit enhancement, fitting RWA’s securitization logic. Vineyards rely on brand premium (geographical indication) and data packaging, with their non-standard attributes making revenue rights difficult to directly tokenize, forcing them toward the indirect path of “data asset shell” (DAS).

5.2.3Technical Path: On-chain Value Closed Loop vs Off-chain Rights Fragmentation

Longshine achieves rigid binding between physical assets and on-chain value through “Two Chains One Bridge.” Malu’s blockchain is only used for data attestation and credit enhancement, failing to build a closed loop between revenue rights and tokens, resulting in both producers (farmers) and consumers (NFT holders) being excluded from value distribution.

Conclusion: Triple Contradictions Shape China’s RWA Polarization

Policy is the ceiling: Hong Kong sandbox provides Longshine with a “securitization testing ground,” while mainland prohibitions force Malu toward “de-financialization” survival.

Assets are the foundation: The industrial standardization attributes of charging piles naturally fit RWA, while agricultural non-standard assets need to rely on policy privileges (such as geographical indications) to partially achieve digitization.

Technology is the adhesive: Longshine uses technology to connect cross-border compliance (ZKP cross-chain verification), while Malu’s technology only serves regulatory compliance (AMC multi-chain attestation), not free value flow.

The practical differences in China’s RWA are actually the result of collision between global financial liberalization ideals and local strong regulatory reality. Longshine chooses “cross-border breakthrough,” Malu is forced into “local compromise,” and both reveal that discussing RWA divorced from policy context is a false proposition in the Chinese market.

5.3 MALU AGRICULTURAL RWA’S CROSS-BORDER IMPOSSIBLE TRIANGLE

The Malu grape project did not choose the Hong Kong sandbox model but was limited to mainland closed-loop operations. Its underlying obstacles are three insurmountable rigid constraints. The core reason is not insufficient technical capability, but deep mismatch between asset attributes, policy compliance, and business logic:

5.3.1Asset Compliance Defects: Agricultural Revenue Rights Cannot Be Cross-border Confirmed

Hong Kong Monetary Authority sandbox requires underlying assets to have verifiable stable cash flows (such as Longshine project’s 9,000 charging piles with annual revenue exceeding 30 million yuan), while Malu grapes lack hardcore asset support for cross-border securitization.

5.3.2 State-owned Data Export Ban and Local Interest Binding

The Malu project’s “Shanghai geographical indication” label makes it a local digital economy model project, with government-led attributes destining it unable to break away from domestic regulatory frameworks.

5.3.3 Business Logic Contradiction: Offshore Costs Far Exceed Domestic Financing Value

The Malu project’s total financing amount is only 10.2 million yuan RMB, while replicating Longshine’s cross-border model requires investment exceeding 7 million yuan in upfront costs (excluding Hong Kong lawyer audit fees), and Hong Kong investors have extremely low interest in agricultural non-standard assets—the sandbox economic model simply cannot be established.

5.3.4 Technical Compatibility: Agricultural Data Cannot Support Cross-border Value Verification

The non-standardization and labor dependence of agricultural production prevent it from building a “data→revenue” on-chain closed loop. Forcibly grafting “Two Chains One Bridge” only amplifies technical distortion.

Conclusion: Agricultural RWA’s “Localization Cage”

The Malu project’s choice is actually inevitable under the triangular deadlock of policy, assets, and capital:

Policy level: State-owned data export red line + local achievement binding = cross-border path sealed off

Asset level: Non-standard agricultural product revenue rights ≠ securitizable financial assets

Business level: Micro-financing vs cross-border high costs = economic model collapse

5.4 STRATEGIC PATH FROM INDUSTRIAL CROSS-BORDER PRIORITY TO AGRICULTURAL GRADUAL BARRIER BREAKING

The Longshine paradigm represents the optimal RWA solution for standardized assets in the industrial era—cross-border arbitrage + technological guarantee.

The Malu path reveals the cruel reality of agricultural RWA: under the existing framework, consumer NFTs are the only compliant outlet, essentially a difficult balance between “regulatory tolerance” and “value incompleteness.”

For agricultural assets to break through the cage, they need to wait for three new infrastructures to mature—rural data property rights legislation (solving ownership confirmation), offshore agricultural REITs channels (solving cross-border issues), AI planting standardization (solving revenue volatility)—which is exactly the ultimate proposition of “Agricultural RWA 4.0” referred to in Malu Grape’s “Pseudo-RWA” Breakthrough Part1

6.CONCLUSION

The Longshine Technology charging pile RWA project has reshaped China’s physical asset securitization paradigm through three breakthroughs:

At the institutional level, constructing a “Hainan WFOE revenue rights isolation + Hong Kong SPV token issuance” cross-border architecture, opening compliant channels in the gap between the “Data Security Law” and Hong Kong’s “Securities and Futures Ordinance,” providing the first sandbox verification for mainland physical asset cross-border financing.

At the technical level, the “Two Chains One Bridge” system (mainland asset chain – ZKP cross-chain bridge – Hong Kong trading chain) achieves precise balance between sensitive data domestic attestation and value information cross-border circulation, with wCBDC atomic settlement more thoroughly eliminating traditional financial settlement risks.

At the ecosystem level, IoT dynamic data replaces fixed asset collateral, enabling 1,600 small and medium operators’ financing approval rate to jump from 37% to 83%, proving that the “data credit generation → fragmented circulation → offshore capital access” path can systematically activate dormant asset value.

However, this paradigm still faces unavoidable challenges:

On liquidity paradox, ERC-1400 tokens due to Hong Kong professional investor clauses and 6-month lock-up restrictions have secondary market liquidity index of only 0.07 (less than 6% of Hong Kong REITs), revealing the deep contradiction that on-chain rights confirmation does not equal free circulation.

On cost structure, dual auditing and cross-border exchange losses push issuance costs to 10%, forming institutional friction.

On industry compatibility, comparing with the Malu grape project shows that industrial standardized assets (charging piles) have stronger RWA compatibility due to stable cash flows and hedgeable risks, while agricultural and other non-standard assets remain trapped by fragmented property rights and cross-border data barriers.

The future evolution of China’s RWA needs breakthroughs in three dimensions:

Policy iteration: relying on Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission’s new “new energy simplified disclosure clauses” and Hainan’s $5 billion QDLP quota to gradually expand asset category coverage.

Technical efficiency: reducing transformation costs by 30% through cross-chain hub standardization and introducing oracles to strengthen non-standard asset on-chain verification.

Ecosystem expansion: prioritizing replication of photovoltaic power stations, cold chain logistics and other industrial scenarios with stable returns, then gradually absorbing agricultural assets after rural data property rights legislation breakthroughs.

The ultimate revelation of the Longshine project is that RWA competition is essentially competition in institutional innovation capability.

For China to form differentiated advantages in the global arena, it must adhere to the trinity strategy of “entity anchoring, technological empowerment, regulatory coordination”—both deepening advantages in cross-border securitization of industrial standardized assets and reserving evolutionary space for non-standard assets like agriculture and consumption under sandbox mechanisms.

Only thus can we truly achieve “from one kilowatt-hour to thousands of industries” capital ecosystem reconstruction in the balance between financial opening and risk prevention.

Read more:

Cross-border RWA Success Story: Deconstructing the Compliance Architecture Behind Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s Sandbox 100 Million Yuan Fundraising Part 1

Cross-border RWA Success Story: Deconstructing the Compliance Architecture Behind Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s Sandbox 100 Million Yuan Fundraising Part 2

RWA Revolution: Complete Guide to Real-World Asset Tokenization Part 1

RWA Revolution: Complete Guide to Real-World Asset Tokenization Part 2

〈Cross-border RWA Success Story: Deconstructing the Compliance Architecture Behind Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s Sandbox 100 Million Yuan Fundraising Part 3〉這篇文章最早發佈於《CoinRank》。