- Topic1/3

51k Popularity

8k Popularity

7k Popularity

2k Popularity

658 Popularity

- Pin

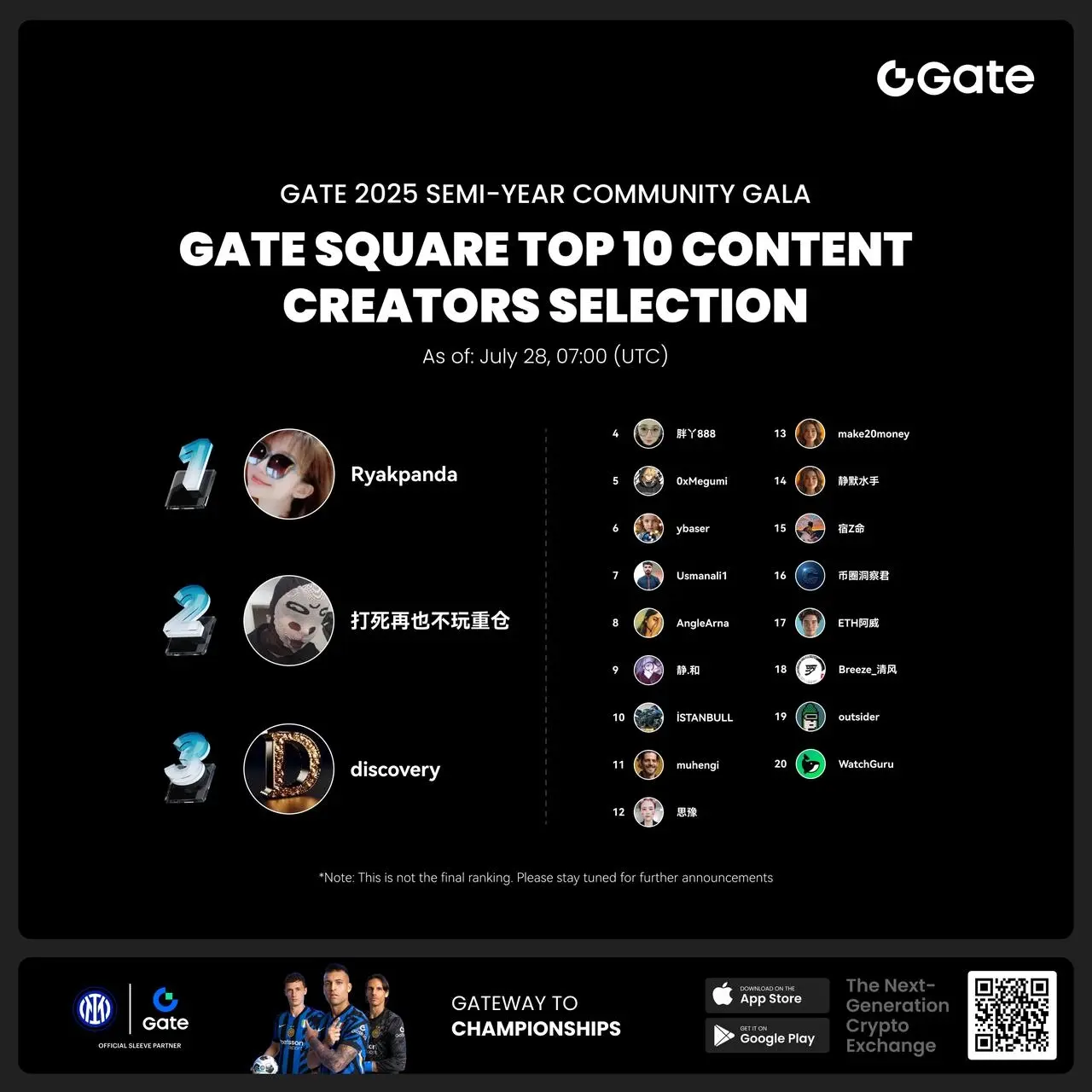

- #Gate 2025 Semi-Year Community Gala# voting is in progress! 🔥

Gate Square TOP 40 Creator Leaderboard is out

🙌 Vote to support your favorite creators: www.gate.com/activities/community-vote

Earn Votes by completing daily [Square] tasks. 30 delivered Votes = 1 lucky draw chance!

🎁 Win prizes like iPhone 16 Pro Max, Golden Bull Sculpture, Futures Voucher, and hot tokens.

The more you support, the higher your chances!

Vote to support creators now and win big!

https://www.gate.com/announcements/article/45974

- 🎉 Hey Gate Square friends! Non-stop perks and endless excitement—our hottest posting reward events are ongoing now! The more you post, the more you win. Don’t miss your exclusive goodies! 🚀

1️⃣ #ETH Hits 4800# | Market Analysis & Prediction: Boldly share your ETH predictions to showcase your insights! 10 lucky users will split a 0.1 ETH prize!

Details 👉 https://www.gate.com/post/status/12322612

2️⃣ #Creator Campaign Phase 2# |ZKWASM Topic: Share original content about ZKWASM or its trading activity on X or Gate Square to win a share of 4,000 ZKWASM!

Details 👉 https://www.gate.com/post/st - 📢 Gate Square #Creator Campaign Phase 2# is officially live!

Join the ZKWASM event series, share your insights, and win a share of 4,000 $ZKWASM!

As a pioneer in zk-based public chains, ZKWASM is now being prominently promoted on the Gate platform!

Three major campaigns are launching simultaneously: Launchpool subscription, CandyDrop airdrop, and Alpha exclusive trading — don’t miss out!

🎨 Campaign 1: Post on Gate Square and win content rewards

📅 Time: July 25, 22:00 – July 29, 22:00 (UTC+8)

📌 How to participate:

Post original content (at least 100 words) on Gate Square related to

From Papal Elections to Polymarket: A Brief History of Prediction Markets

Author: Domer

Pre-modern Prediction Markets

Prediction markets may seem new, but betting on the outcomes of significant events has a long history in politics and other fields.

Informal prediction markets can be traced back at least a thousand years, involving countless events including bets on the outcomes of military wars, bets on who will become the next king, and bets on the results of the Chinese imperial examination that determined whether an individual could enter the civil service.

More formal prediction markets can be traced back at least five hundred years, to the early 16th century in Italy. At that time, people would predict the successor of the next pope through the market and quote the odds in their letters. The first formal "legislation" regarding prediction markets was introduced in 1591 when Pope Gregory XIV stated that anyone who bet on the outcome of the papal secret conclave would be excommunicated from the Church.

In the UK, the earliest recorded prediction markets began in the 18th century, appearing in various coffee houses in London. The Jonathan's Coffee House (which later became the London Stock Exchange) started trading news of parliamentary scandals and changes in prime ministers from the early 18th century. Trading these events became commonplace among the elite, and the odds would even be published in newspapers of the time.

The first recorded "whale" figure was born in such an environment, and that is Charles James Fox, a member of the British Parliament. Since at least 1771, he invested a significant amount of money in predicting political events, including betting on whether the Tea Act would be repealed. In fact, he likely also bet on who would win the American Revolutionary War. Ultimately, he went bankrupt, and his father had to provide tens of millions of dollars (adjusted for inflation) to rescue him. Some may note his similarities to a modern, unknown American politician.

Betting in the U.S. prediction markets can be traced back to at least the early 19th century. James Buchanan, who later became president, wrote that in 1816, he lost three plots of land due to a failed election wager. During this era, we also have the first recorded American "gambler": John Van Buren. He was the Attorney General of New York and recorded over 100 bets in the mid-term elections of 1834, totaling $500,000 (adjusted for inflation). His father, Martin Van Buren (who was also a recorded election gambler), was serving as vice president at the time.

The more formal prediction market in the United States is not the cafés of London, but rather centered around the billiard halls of New York City. The first major dispute over rules (or as modern gamblers might call it: rule corruption) occurred in a billiard hall. The election of 1876 was a fierce argument. There were more violations than there were blood tests for Hilaros, and the final result was delayed for months. As a result, "Old Smoky" Morrissey, who operated the largest billiard hall in New York City, decided to refund everyone's bets, but with a slight alteration: he kept the commission. He was a well-known boxer and a rival of Butcher Bill, so I’m not sure if anyone had too much controversy over this arrangement.

Like London, the odds for the U.S. election in New York are often cited by journals. At that time, public opinion polls had not yet emerged, so betting odds were often the best indicator of sentiment. In fact, newspapers sometimes published the names of bettors and the amounts they wagered. This can be considered the first predictive market ranking.

It wasn't until 1936 that Gallup polls replaced betting odds as a reliable indicator for journalists. After that, the reporting of odds sharply declined, and during and after World War II, any betting markets in New York became taboo, only to be replaced by informal personal wagers decades later.

Modern Prediction Markets

The betting industry began to gamble on elections (the precursor to peer-to-peer prediction markets) in London in the 1960s, with Ladbrokes being the bookmaker at the time. They offered (extremely poor) odds during the Conservative Party leadership contest. The 16/1 odds allowed this candidate to win the race. The tradition of the British regularly betting on elections, with (almost) no surprises, continues to this day, and the UK has the largest peer-to-peer betting market in the world—Betfair.

Betfair will launch prediction markets for the most high-profile elections and political events, including the famous Brexit. However, the vast majority of its trading volume comes from sports events. Overall, in the UK, betting on event outcomes and politics has become normalized. You can walk into any betting shop in a major city and place a bet of a few pounds on almost any significant political event you wish to wager on. If you fancy yourself a great politician, you can also run for office and bet on yourself to win (as more than one candidate has successfully done!).

In the United States, the situation is sometimes good and sometimes bad, but most of the time it is still considered normal.

The Iowa Electronic Market was launched in 1988 as an academic experiment associated with the University of Iowa. The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) is the government organization that regulates futures trading, and it did not explicitly allow or prohibit such trading, but sent them a letter indicating that as long as no one holds a position of more than $500 in the market, they would not take any action against them. This was the first site to adopt 0-100 pricing. If you win, you will receive $1 per share. If you lose, you will receive $0. The IEM started small and intentionally maintained a small scale, only establishing a few markets and having few users. It was difficult to bet more than a few dollars on their site (let alone $500). Although it still exists, it is more of a historical footnote than a serious market.

Intrade / Tradesports was launched in 2002/2003, with some funding provided by renowned American billionaires Paul Tudor Jones and Stan Druckenmiller. It is a website that offers peer-to-peer binary contracts, which are traded based on the outcomes of events. Similar to IEM, if you win, the contract is worth $10; if you lose, the contract is worth $0. The site is located in Ireland and, starting in 2005, reached a tacit agreement with the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) that if the site prevents Americans from trading traditional futures contracts (such as the prices of gold, oil, and other heavily monitored and regulated commodities), the U.S. government will not pursue them. During the presidential elections in 2004, 2008, and 2012, the site became the preferred choice for people seeking political odds.

At that time, the public's sensitivity to data, statistics, and numerical analysis was not as high as it is now, so the market size for such content was not large compared to public opinion polls. Nevertheless, Intrade's CEO, John Delaney—an unwavering advocate for prediction markets—frequently appeared on the American business television program CNBC, explaining event prices on his website and promoting prediction markets more broadly. In 2011, he tragically died while climbing Mount Everest.

A few weeks after the 2012 election, the U.S. government launched an attack on Intrade on the grounds of violating a 2005 agreement (which stipulated that Americans could not trade oil/gold/other commodity futures). As a former user living in the U.S. at the time, I can personally attest that none of these markets allowed Americans to engage in any trading. However, Intrade chose not to engage in a lengthy and costly legal battle with the U.S. government (even winning would still mean losing), but instead expelled all Americans and declared bankruptcy a few months later.

In addition to launching the first serious prediction market that allows large-scale participation by U.S. users, Intrade is also known for two famous "whales": the McCain "whale" and the Romney "whale". Each of them accumulated huge positions in their competition against Barack Obama. Unlike the French "whale" that appeared on Polymarket years later, actively betting on Trump's victory in 2024, these two gamblers lost all their money and poured the winnings onto everyone betting on Obama.

In 2010, a movie box office futures market named Cantor Exchange (after its parent company Cantor Fitzgerald) briefly existed and received full approval from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). I was one of the first to join. The film industry was vehemently opposed to the idea and immediately launched a strong lobbying effort against it. This approval lasted less than two months before it was banned by the U.S. Congress. The two types of futures banned in the U.S. are onion futures and movie box office futures (the reason it's called onion futures is that in the 1950s, some greedy merchants nearly bought up all of the onion supply in the U.S. and monopolized the market). Interestingly, Howard Lutnick, the long-time head of Cantor Fitzgerald, is now the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury (this article was written in early 2025).

PredictIt - the successor to Intrade in the US, uses the exact same template as the Iowa model: they received a "no-action" letter from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) when they launched in 2014. A US political consulting firm named Aristotle collaborated with Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand to create the site. They set a cap of $850 on each position (which is the cap for IEM, adjusted for inflation). PredictIt became the most cited source for odds during the 2016 and 2020 elections. The CFTC withdrew its "no-action" letter regarding PredictIt in 2022, after PredictIt began providing market data that the CFTC deemed too gambling-focused. This included the number of tweets politicians released each week. One of the market data points was "How many tweets will Andrew Yang post this week?" which led to threats against Andrew Yang to post more tweets, ultimately resulting in a lawsuit from law enforcement. In the end, PredictIt struggled to break free from the regulatory scope of the CFTC during its startup phase and ultimately paid the price. There are now rumors that if the CFTC approves, PredictIt will attempt to restructure, rebrand, and relaunch as a regulated site.

2020 witnessed the birth of contemporary prediction markets: Polymarket and Kalshi. In 2020, both of these markets were still very small.

In 2020, some other cryptocurrency websites also emerged, and their prediction markets were quite rudimentary. Several companies divided the lowest trading volume of the presidential election: Augur, Catnip, and FTX, among others. On these sites, the cryptocurrency tokens you purchased would be stored in your crypto wallet, and if the candidate you supported won, the token would be worth $1; if the candidate lost, the token would be worth $0. All of these markets have been replaced by Polymarket and are almost non-existent, except for a few jokes or memories. Notably, FTX ran afoul of the law for some unrelated reasons. As a side note, one of my friends (theoretically) amassed huge debts because of SBF’s registered bets on the Trump 2024 election in Alameda County's books, to the extent that this money became an item in the bankruptcy filings.

Current Industry and Future

By 2025, the prediction market will be dominated by two giants: Kalshi and Polymarket. Strictly speaking, they have two user groups that cannot interact with each other, which often leads to slight differences in event prices between the two markets.

Kalshi is a website/application with hundreds of markets. After a rapid launch from Y Combinator, Kalshi received full approval from the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) in 2020 to trade markets based on events, excluding elections. In 2022, CFTC commissioners voted to formally reject Kalshi's application for election contracts, and Kalshi subsequently sued the CFTC. In 2024, after a Supreme Court case ended Chevron deference and severely weakened the powers of agencies like the CFTC, the judge ruled that Kalshi could list election contracts. In 2025, Kalshi further pushed legal boundaries by allowing betting on sporting events from the perspective of event contracts. Currently, they are being sued by multiple states in the U.S. Kalshi does not allow non-U.S. citizens to participate, and all bets are denominated in U.S. dollars.

At the same time, Polymarket is a cryptocurrency-based website with hundreds of markets. All transactions are conducted on-chain, and all bets are processed through smart contracts, which are verified by a third-party verification program called UMA before payment. Polymarket paid a fine to the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) in January 2022 and agreed to prohibit U.S. residents from using its website. Although they also use cryptocurrency, bets are denominated in the stablecoin USDC operated by Circle. Cryptocurrency price fluctuations do not affect users' bets. The website operates on an Ethereum L2 called Polygon. To use a rough analogy, Polymarket is like an application, Polygon is like the operating system, and Ethereum is like the phone manufacturer.

Both companies were founded in New York by ambitious founders of similar ages. Both companies have ambitious capital and a number of well-known investors and advisors. The competition between the two is comparable to that of Uber and Lyft, or Visa and MasterCard.

Due to the political turmoil in the United States (especially the unprecedented collapse and the late withdrawal of a presidential candidate from a certain party), the media has become more focused than ever on betting odds to understand the world. As a result, the trading volume of each company and the overall trading volume in the prediction market experienced explosive growth in the 2024 election.

A story that has particularly captured public attention is my discovery and conversation with this "French whale." This mysterious gentleman became the largest prediction market gambler in history within just a few weeks. He bet tens of millions of dollars on Trump winning the 2024 election, significantly shifting the odds in Trump's favor. In the end, his prediction was correct.

The future of these markets will likely depend on how each company competes for dominance. However, the most probable outcome is that by 2028, both companies will become giants, while smaller companies will try to get a piece of the pie.

Regulatory issues remain a challenge in the United States, especially considering that Kalshi is challenging the legal boundaries in the sports sector, as well as the fact that the founder of Polymarket was raided by the Department of Justice at the end of President Biden's term.

In recent years, with the surge in trading volume in prediction markets, the demand for emerging innovative markets has also reached an unprecedented high. This presents both opportunities and challenges: regulatory issues have now become the biggest obstacle in the industry. This will inevitably delay the next significant growth peak of the market, as new users may feel frustrated by the need for complex expertise to address this issue.

Overall, although prediction markets have been stifled throughout history, they will continue to emerge whenever there is an opportunity. When two people disagree on an important issue, the best solution is to use money to support your statements. By integrating all these statements and funds into a vast market, wisdom can be unlocked.

Final Thoughts

The future is unknown and unpredictable.

Do not treat prediction markets as a universal solution for forecasting future trends, but rather as a better flashlight that allows us to foresee the future. The market is certainly more effective than expert opinions, and even better than opinion polls, because the market itself encompasses opinion polls.

As the public in Western democratic countries becomes increasingly polarized, people are getting news from increasingly biased sources, predicting that the market can and will break the partisan nonsense and reveal the truth.